Theories of Political Development consider polities of the Third World from underdevelopment to development.

The process which facilitates their efforts to achieve their social ends is ‘development’.

The factors which hinder them in this direction are responsible for their ‘underdevelopment’. For this the Marxist and neo-Marxist scholars have advanced ‘dependency theory’ to explain the phenomenon of underdevelopment.

Liberal and Marxist thinkers give different accounts of the factors of underdevelopment. Various attempts have been made to develop theories, approaches, paradigms and models of political development, which rid polities and societies of underdevelopment. More important among them are briefly discussed below.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Dialectical Theory of Political Development:

W.F. Riggs is one of the greatest authorities on political development. Though he calls his formulation only a ‘paradigm’, yet it can be regarded as a ‘dialectical theory of political development’. According to him, increased structural differentiation is the key variable of political development. He is mainly a structuralist, and maintains that governmental or political structure can be borrowed or transferred independent of cultural considerations. He regards governmental institutions and practices as ‘technology’.” It can be transplanted anywhere across political systems and political cultures.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The key to political development is the ability to shape and be shaped by environment. Men or societies want political development to enhance their freedom of choice and pursue goals, called ‘political goods’ by Pennock. The ratio between the two variables – ability and environment, provides one of the many tests of the level of development attained by a system.

Political development involves a system’s capacity to absorb and utilise more and more information from its environment. Its goal is to respond to this information and to bring about change to satisfy its needs, and to enhance the range and diversity of goals that can be satisfied.

With a view to explaining the phenomenon of political development, he makes use of the contributions of developmental scholars. He presents them in form of a few theoretical propositions. According to Riggs, a set of operations governs the phenomena of change among dependent variables.

It appears in response to inputs generated by the independent variables. The system has to stabilize at different levels of development leading to an equilibrium necessary for a system to go ahead. If a system has higher level of differentiation, it could absorb basic changes. More differentiation means more capacity to absorb changes and face challenges.

There are three independent variables:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) Challenges posed by environment,

(ii) Efforts to be made by the existing system to work better, and

(iii) Efforts to change the existing system.

Dependent variables available to the system are:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) Performance level,

(ii) Level of differentiation, and

(iii) Degree of ‘integration’, absorption.

Political development is interaction and interplay among these variables. But he prefers the use of the term ‘political development’ in plural like ‘polities’. He regards ‘development’ as merely a label for a cluster of activities, operations, and changes. Riggs adopts the three criteria or properties of Pye’s syndrome of political development: differentiation, capacity, and equality, with a typology of developmental stages based on key governmental technologies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These governmental technologies are transferrable cross-culturally or systems can have another functional equivalents. These governmental technologies or structures are important and independent of any cultural sway. They can be possessed, used and operated like telephone, radio, TV or camera irrespective of political cultures.

According to him, technological changes in politics and administration do have sudden qualitative jumps or thrusts, and create structural differentiation. They do bring in problems in the wake. Other functional categories, besides structural categories, can have quantitative measurements. Political development can be explained by technological (differentiational) advances in government. Of course, increased structural differentiation, while solving some problems, also creates new difficulties in the direction of proper coordination and integration of the system.

This structural differentiation and its advance has to help maintaining a balance between ‘capacity’ (c) and ‘equality’ (e). Capacity is the ability of a political and administrative system to adopt collectively authorised goals and to implement them. Equality (e) is extent of participation and sharing of benefits available during the course of implementation of goals. Thus, differentiation, caused by technological structures is related to equality (e) and capacity (c).

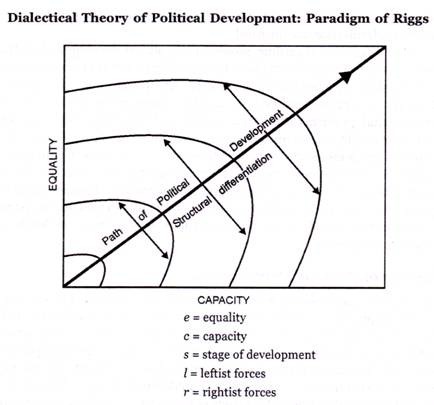

Diagram presents paradigm of dialectical theory of political development. System treads on the diagonal path of political development. This path, made of structural differentiation, is cut at various points or stages (S1, S2, S3,) when the system arrives at certain balance or equilibrium between forces of equality (e) and capacity (c). The balance or equilibrium between the two provides a developmental thrust or leap forward on the path of structural differentiation.

The system moves ahead. The two legs of political development are capacity (or rightist forces) and equality (leftist forces). As such, the system advances further on the two legs of structural differentiation. If the lines show more area covered by them towards right, the equilibrium will be disturbed. There would be imbalance and the system would be in favour of rightist or capacity (elitist) forces making arrowed crosscutting line longer towards right or capacity. So will be the case with leftist or equality (mass) forces.

If the system moves towards left, it would mean there are much more demands on the system to participate in the decision-making or for sharing of benefits, and the forces of capacity thereby have reduced strength to check them from putting more pressure on the system. Structural differentiation is the key to deal with both the goals of equality and capacity.

‘Conflicts between these goals are most acute in transitional stages’, Riggs observes. There is hide-and-seek in attaining either of the two goals. Hence, maintaining equilibrium is necessary to move onwards along the path of political development which can be possible only by and through structural differentiation attached with governmental technologies.

The equidistance shown by arrows r – 1 at S1, S2, S3, is rarely maintained in actual practice. Like thesis and anti-thesis, both equality and capacity oppose each other. Structural differential is created out of their conflict or struggle and appears in form of synthesis. Therefore, it has been called as ‘dialectical theory of political development.’ As soon as synthesis appears, the system begins to take strides over the long and tiresome path of political development.

The developmental process of thesis – antithesis – synthesis continuously goes on both in developing as well as developed countries. The environment or ecology of the whole political system presents the background for inventing or developing appropriate governmental technologies. Once such governmental technologies are in hand, reproduction or existence of circumstances in which they were made and developed is not necessary. These technologies can easily be imported, and they bring about qualitative change in the political system.

As a result of import of these governmental technologies, radical changes are taking place in various countries of the Third World. Impact of foreign aid, loan, transfer of technology, training, etc., can be seen in this perspective. Although, Riggsian dialectical model deals with the processes of internal differentiation, yet it can also explain a lot of changes taking place outside of a political system.

Both leftist or rightist forces can make use of these governmental technologies. For example, bureaucratic apparatuses can be used both by a ruling coterie or a popular government monocracy or democracy. But development ensues only on creation of an equilibrium. Structural differentiation appears, only at balancing or midpoints and generates development by bringing about an equilibrium between forces of equality and capacity. In the absence of balance, political system often falls into development-trap. It means the political system hands over itself either to the forces of capacity or equality, at the expense of each other.

To sum up, an increase in the level of differentiation (d) makes it possible to achieve higher levels both of equality and capacity. But such an increase can be generated endogenously only when a balance between capacity (c) and equality (e) prevails. The system falls into ‘development-trap’ when it resorts to either of the two, and stop all structural differentiation.

Only the balance between the two enables the system to heighten the level of structural differentiation, and realise higher degree of capacity and equality. Western countries so far had endogenous development, but non-western countries resort to exogenous form of development. They can go right or left and also maintain a balance between them for their people as a whole. Each position, obviously, has problems peculiar to it.

Thus Riggs has been able, to a large extent, to coordinate various studies on political development. With the help of his developmental paradigm or theory, crises, observed by Pye, can be explained. It can also explain Huntington’s ‘political decay’, or Eisenstadt’s ‘breakdown’. Halpern’s ‘will and capacity’ also can stand closer to it. Huntington’s ‘institutionalisation’ can be taken as a form of structural differentiation. Various explanations over political development can also be accommodated within the perspective of W.F. Riggs.

However, Riggs appears too much dependent on the variable of structural differentiation. His theoretical paradigm requires empirical verification at the hands of scholars and political actors. Surely, it has potential of empirical verification, though it also raises several other issues and questions.’

Developmental Approach: Almond and Powell:

Like Riggs, but on a larger and wider empirical level. Almond and Powell (Comparative Politics: A Development Approach, 1966) also have formulated a developmental approach for studying modernising societies. They have made much more use of concepts like political system, political culture, secularisation, socialisation, subsystem autonomy, environment, etc. In the presentation of an exhaustive typology of political systems ranked on a scale of political development, they have gone quite close to the formulation of an empirical theory of political systems.

Communist Model of Political Development:

The communist model of political development is based largely on Marxist-Leninist ideology. The source of motivation for political development, accordingly, lies in industrialisation, monopoly over forces of production, exploitation of labour, class consciousness and organisation of the working classes. Lenin is more important than Marx regarding political development. He led the Russian revolution and had to confront problems of development in backward countries.

Lenin showed the path of development for Russia by the establishment of dictatorship of the proletariat by resorting to revolutionary means under the leadership of a disciplined political party. After him, Stalin succeeded in industrialising the Russian society by repression and violent means. Thus, Russia attained modernisation within 30 years which the Western countries could achieve after the end of about 200 years, and became a superpower.

Stalin concentrated his attention on the making of Russia alone, and did not take interest in the development of other countries. Many other countries turned communist, but they did not blindly follow the Russian path of development. But the blueprint of political development was almost common for them all. The political set-up of all communist countries remained similar.

In colonial and backward countries, Lenin gave support to bourgeois-national movements so that after attainment of freedom they would have economic and political development under Russian direction. But many countries, including China, did not do so. In fact, within the communist camp, there were many models of political development, such as, Chinese, Yugoslav, Cubaic, Rumanian, etc. Thus, before developing countries, there were two broad patterns of political development – western and communist.

Often these countries, due to lack of resources, skills, time, etc., and role of politics, opted for the Russian or Communist model, but, they found themselves unable to pay the cost in human terms, and also were not ready to give up nationalism and democracy as a matter of faith. This model collapsed with the collapse and fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Only a few countries now claim to follow it.

Dependency Model:

The exponents of ‘dependency theory’ argue that third world countries had remained underdeveloped because their social and economic development was conditioned by external forces like colonialism and exploitation. Uneven political development is a universal phenomenon.

Scholars have tried to explain it in two forms:

(a) Dependency model, and

(b) Centre-periphery model.

Andre Gundre Frank (Comparative Government, 1969) in the context of Latin American countries raised the fallowing three issues:

(i) Why is there uneven development in the world?

(ii) Why are they now underdeveloped countries suffering from failure of internal market?

(iii) Has the phenomena become a fundamental feature?

Frank is aware that Great Britain and the USA took respectively 183 and 93 years in attaining industrial development. But the developing countries are eager to have it in about 30-40 years. Many factors can be attributed to it. Mercantalism held its sway from 1500 to 1770, industrialisation took another hundred years from 1770 to 1870, capitalism ruled over from 1870 onwards. But it does not mean that emerging nations should undergo the same process. Paul Baran, Frank Curzy, Gultang, etc., have sharply criticised the Western model of development. Andre G. Frank rejects the classical explanation that the poor are poor because they are vice versa.

The fact revealed to us is that the West started developing from 1550 to 1770 at the cost of Latin American countries. There was no mercantilism in favour of these countries. They were fiercely and fully exploited, and trade went against them. Walter Rodney and B. Cuings confirmed Frank’s conclusions in the context of Africa and Asia. Thereafter, industrialisation took place in Europe. It made possible for these countries to have capital accumulation.

They established their political authority over them, and had a free hand in their total exploitation. After the World War II, they were politically free, but remained still under the yoke of neo-colonialism. Thus, inequality and exploitation, which had already been existing, continued to prevail unabated.

Two reasons can be attributed for it:

(1) There is unequal exchange between the owners of production and producers of raw material. The imperial or colonial masters exploited them in their own way, and also compelled the producers to produce raw material required by them. Thus, all benefits went to the owners of production.

(2) The world was assumed to be one economic order. As such, the underdeveloped countries were forced to produce raw material and were not allowed to manufacture finished goods.

All this led to dependence on imperialist and neo-colonial powers. It caused formerly rich Latin countries to grow poor and the poor European countries to become rich. So much so, that rich countries like Brazil (and India) became poorer, their natural resources were exploited by countries of trade and industry, with less and less return to the producer. Frank observes that USA, Canada, and Russia were also colonised, but came out of exploitation-net of European countries earlier, and joined the same forces of exploitation. Russia and later China became communist.

Paul Baran also finds that the developed countries are taking away all economic surplus, making the developing countries still more dependent. A large number of these countries are politically and juridically free but not ‘developed’ as yet. They are actually under neo-imperialism – politically free but economically still under their tight control. The gap between the developed and these developing countries is increasing every day at the rate of 14 per cent. The rate of development in these countries is 3-2 per cent only.

Frank adduces three major causes of their plight:

(a) Economic aid is another form of exploitation, given at wrong time for a wrong sector;

(b) Technical aid is second rate, outmoded and rejectable. Goods produced as a result of this aid cannot be sold anywhere; and

(c) Multinationals are creating havoc everywhere, taking all profits, and encouraging conflicts in the host countries.

Das Sandoz further adds that besides economic dependency, there is evidence of political dependency because economic superiority provides clout to have high hand in political decision-making, both at national and international levels.

Centre-Periphery Model:

Dependency model has not fully satisfied scholars of economic and political development. It has taken into account only external factors and conditions of underdevelopment. Internal causes too contribute to the underdevelopment of these countries. Frank and some others appear to have adopted a fatalist and pessimistic approach in the sense that these undeveloped countries can never hope to become developed.

It appears that they have readily applied their findings taken from Latin American countries to all developing countries of the world. Some of these countries may have different reasons for their underdevelopment, such as, explosion of population is consuming all of their surplus, profits, etc., and nothing is left for making further investment. Wastage and heavy cost of administration can be extra reason for their plight.

However, another plausible explanation has come in the form of centre-periphery relationships (see the following diagram):

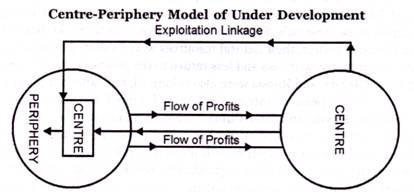

Every developing or underdeveloped country has a centre and its periphery. Main cities and trading towns are called as centre, and villages which produce raw material are treated its periphery. In them, the centre exploits the periphery as usual. Besides above, in the field of international relations, the advanced or developed countries form the centre, and the developing countries constitute the periphery. The developed countries or the centre exploits the periphery or the developing countries.

The centre of centre (developed) countries enter into contract or collusion with the centre of periphery (developing) countries, and the drain of continuous exploitation goes on. The periphery (producers of raw material) of periphery countries is doubly exploited. First, the centre of developing country itself exploits the periphery.

Second, the centre or advanced countries exploit the centre of periphery countries. Collusion takes place owing to profit-motives of the centre of periphery (developing) country. The centre of the developed country brings the centre of the periphery (under developed country) on their side by giving them greater advantage, as multinationals give more profit to them, but in fact consume all of their scarce resources.

Samir Amin in Accumulation on a World Scale:

A Critique of Theory of Underdevelopment, 1974, has pointed out that the industrialised countries and the less developed countries are integrated in a manner that capitalism fails to perform its role of development. There is unequal exchange in the international trade. The West is playing the same role through WTO, IMF and others. Advanced countries invest their capital in the former colonies and use them as suppliers of raw materials and labour at throwaway prices. They are potential markets for their manufactured goods at the market prices.

Still, the Centre-Periphery model lacks a fuller explanation. It is not necessary that the periphery always cooperates with the centre there can be contradictions between the two, and they may not cooperate at all. It tries to explain the tentacles of neo-colonialism, but much of political development remains to be accounted for.

Kothari-Mehta Perceptive:

Few are satisfied with the present models of political development. Rajni Kothari has found the various models of development as highly dangerous and suicidal by nature. Modern science, modern technology, and modern communications are all based on fragmented approach to human problems. Conflicts have become global. Inequity has increased, and very little has been done systematically to solve it. Particularly, ‘thinking in the Third World is bereft of systematic inquiry into the fundamentals of life.’

Man has virtually surrendered his freedom at the altar of new religion called modernity. Kothari believes in presenting a wide and all-embracing framework that wears together the concerns of science, philosophy, culture, and religion from alternative civilisational perspectives. His is a holistic approach, leading to a larger process of self-realisation or certain basic values. He rejects relentless consumerism as indicator of development.

There are certain basic postulates of the alternative model of development proposed by Kothari, such as:

(i) Removal of poverty,

(ii) Equity through local self-reliance entailing plurality,

(iii) Self-reliance and Decentralisation,

(iv) Development takes the form of liberation,

(v) Endogenous science and its use for man,

(vi) Building of a new road to prosperity, and

(vii) Restoration of original symbiosis between science and nature which has been disturbed as a result of making science an instrument of exploitative technology. In fact, these postulates make up the action plan of his environmental perspective.

But the basic features of his approach are following:

1. It adopts a holistic view of development.

2. It is concerned with a structure of equity that ensures autonomy and self-reliance of diverse entities in place of a structure of dependence that is sustained by the promise and transfer of technology to enable others to catch up.

3. It puts emphasis on participation.

4. Its main accent is also on the importance of local conditions and the value of diversity.

Kothari rejects the prevailing alternatives of liberal democracy as well as state socialism. The former is dominated by machine-politics whereas the latter is actually dominated by a small bureaucratic elite. But both are found authoritarian. Nobody is really ready to come to rescue the developing nations.

The number of underdeveloped and developing countries was 77 (known as group of 77) in about a decade ago, but increased to 120. The internationally accepted target of 0.7 per cent of GNP to be given by the developed countries to developing countries has fallen below 0.35 per cent of GNP achieved in 1975. Few are really ready to appreciate that ‘lasting peace and equitable prosperity are really two sides of the same coin.’

Mehta also finds various developmental approaches as ‘vulgarisation of what was a typically European experience into a universal experience.’ According to him, change always takes place against a background: ‘it is a result of an interaction of the subjective, objective and the ethical conditions, and cannot transcend its temporality.’ Each society has a peculiar genius and distinctive nature and temperament of its own.

Therefore, only those forms of modernisation are likely to succeed which spring from a fuller and holistic understanding of the process of change inherent in that society. In his concept of modernity the old subsists side by side with the new. There can be no denial of the past, rather the socio-cultural should prevail over everything else. The process of modernisation, for Mehta, is in fact a search for and development of one’s own identity. In sum, only those forms of modernisation are likely to succeed which spring from a fuller and holistic understanding of the inherent process of change in society.

Welfare Model of Development:

Welfare state model is a modified version of the liberal view which had have originally been supporting the market society model. The idea of welfare began with Prince Bismarck (1815-98), the German Chancellor (1871-90), and, Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928), British Prime Minister of Great Britain (1908-16). Fuller expression to the idea of welfare was given by the Beveridge Report (1942). Implementation of this report turned England as be a model welfare state. It resorted to the policy of progressive taxation.

Those who had higher income and wealth were required to pay higher rates of taxes. In effect, it is a method of redistribution of wealth in society. Eventually, France, Italy, Germany, Sweden, Australia and New Zealand followed the model in degrees only. Other countries owing to shortage of resources adopted it on a subdued scale. The functioning of the welfare state was adversely affected due to bureaucratic inefficiency and rampant corruption.

Gandhian Model of Development:

Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) was primarily a moral philosopher. He did not advance any theory of development. He gave precedence to morality over politics. Politics for him was an instrument of achieving moral goals and self-realisation. His role in the independence movements of India was aimed at securing moral regeneration of India.

He never wanted India to emulate the ways of the Western civilisation: consumerism, materialism, competition, arrogance, selfishness, concentration of wealth, and exploitation. He stood for self-control, renunciation, moral strength, bread labour, truth, non-violence, and compassion. This model is highly appreciated and eulogised, but has hardly been practised. His techniques of mass mobilisation and struggle are a great contribution to the philosophy of social change.

LPG Model of Development:

This is the currently prevailing market society model of development. It has revolutionised economies, cultures and communities the world over.” It has created the problems, which the advocates of sustainable development and environmentalists claim to concentrate on and solve them.

Sustainable Development and Environment:

Development is a man-made positive phenomenon. It stands for the improvement of human life in all spheres. But higher production under various forms of development involves exploitation of natural resources. Gigantic machines consume huge energy resources, and cause pollution, disease and shortages. In a sharp reaction to them, there is demand of ‘sustainable development’.

Its idea was floated earlier during the Earth Summit held in Stockholm in 1972. It expressed a serious concern over the rapid depletion of the exhaustible natural resources. Later it was elaborated in the Bruntland Report, entitled Our Common Future, published in 1987. The issue of’ sustainable development’ was warmly supported and upheld by the environmentalists.

Environmentalism or ecologism’ appears to be a natural outcome of the demand for sustainable development. It redefines relationship between man and nature, and among human beings. It insists that man is no more the ‘master’ of nature. Man is one of the partners with all other living organisms.

There was no problem at the beginning of human civilisation. With the increase human population from merely 20 crores to over 5 billion, rise in the level of consumption, superiority of science and technology, and limitless demands of man over and from nature, the equilibrium between man and nature has been completely lost. There is fast depletion of natural resources.

Man has to follow what E.F. Schumacher has said in his Small is Beautiful (1973). Otherwise man would be digging his own grave. Shumacher has warned that the earth and its non-renewable resources should not be confused with the conventional concept of ‘capital’. Advanced countries, particularly, the USA and others, are inflicting great harm on the earth. They have to change their lifestyle, transport system, consumption of energy, food habits, and the like.

Reacting to them, millions of people in the advanced countries are now connected with ‘Green movements’ and ‘Green polities’. They want to save mankind from imminent catastrophe – greenhouse effects, global warming and ozone depletion. Man has to dismantle large-scale manufacturing system and change over to smaller-scale manufacturing systems to be supervised and controlled by self-governing local bodies. Population, consumption, concentration of wealth etc. have to be reduced sharply.

They all remind the UN slogan that, “We have not inherited this earth from our forefathers; we have borrowed it from our children.” For this, all have to be: “Neither left nor right, but forwards.” We have to prepare ourselves for a better future of mankind. From time to time, the UN and other world bodies discuss these matters, but advanced countries fail to comply with directives and recommendations.